Dynamics Parameters Estimation

Introduction

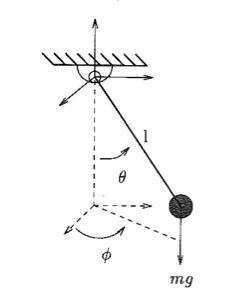

For robotic manipulators such as the 3-link arm shown in Figure 1, having accurate models whether it be kinematic or dynamic models is necessary for accurate operation of the robot. In this project I have focused on estimation of the dynamic model parameters, a task known as system identification in the controls literature. Having an accurate dynamic model allows the robot to reason, and plan about the forces applied to it and by it onto the environment. One common external force is gravity. By compensating for the forces exerted by gravity, a mode known as gravity compensation, it will be able to remain stationary in the absence of outside forces. In addition, a user moving the manipulator by hand would perceive that arm feels effectively weightless. Using the dynamics model it is also possible to identify if there is any unexpected forces imparted on the robot by its environment effectively allowing the manipulator to know when and how it is making contact.

Figure 1: 3-link manipulator [1]

Dynamic Models

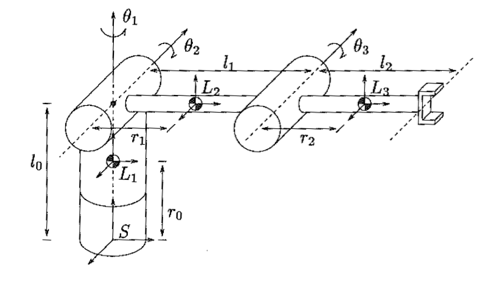

In speaking about the dynamics for a system, the quantities of interest are the velocities, accelerations and forces imparted on it. In basic high school physics, these quantities are what one would normal expect, expressed in units of m/s, m/s^2, and Newtons. However, reasoning in terms of coordinates in normal Euclidean space can be awkward for constrained systems. In these cases, it is often more intuitive to think of the concepts of forces, velocities, and accelerations in terms of the system’s constraints. For example, in the case of a pendulum (Figure 2) involving a mass m on a string of length L, the equations motion for the mass with the constrain that its position is constant with respect to the pendulum’s center are involved and nonintuitive. But if we speak about the system’s motion in terms of the already constrained generalized coordinates theta and phi, then velocities with respect to these coordinates are again natural and intuitive.

For the case of a robotics manipulator, these generalized coordinates can be chosen to be robot’s joint angles. The ‘forces’ affecting motion in these coordinates correspond to torques applied by the manipulator’s motors. Abstractly, when all necessary parameters are given, the equations of motion take as input the joint angles along with its first and second derivatives to produce as output a set of torques on the joints. These are the torques that need to be applied to produce the joint accelerations for a given joint velocity and configuration of the robot. However, these correspondences are only as good as the parameters that govern this model. Ultimately, reality has the last say on what the equations motions and parameters should be been to produce a given motion.

Model Parameters

In general, the number of parameters to describe these equations of motions depend on the choice of model. For this project, each link of the robot is treated as a rectangular prism, with the moments of inertias described in terms of the center of mass. The parameters that has to be specified for each link are the dimensions of this rectangular prism (length, width and height) and the link mass. However, depending on the robot arm’s structure and range of motions, some of these parameters does not have to be specified. To estimate these parameters the general idea is to fit the model’s parameters as best as possible to recorded data of the robot’s dynamic behavior. In terms of what’s been described so far, the robot’s joint angles, joint velocities, and joint accelerations will be recorded along with the commanded torques.

Problem Formulation

To scope the task for this project, and to explore performance of the optimization algorithms with respect to these models, estimation of the dynamic parameters will be performed on a simulated system. Using data generated from this ideal system with known parameters, the task is to recover the correct parameters under various conditions including variations in sample size, starting estimates, and noise in recorded data.

[1] R. Murray, L. Zexiang, S. Sastry. A Mathematical Introduction to Robotic Manipulation. 1994.

[2] J. Hollerback, W. Khalil, M. Gautier. Springer Handbook of Robotics. Chapter 14. 2008.

Figure 2: A simple pendulum [1]