When we want to show that a language is undecidable, we want to somehow rely on using the fact that the Halting Problem is undecidable. So here's how we want to show that a language L is undecidable. Suppose L is not undecidable. Then there is a decider, say D, that decides L.

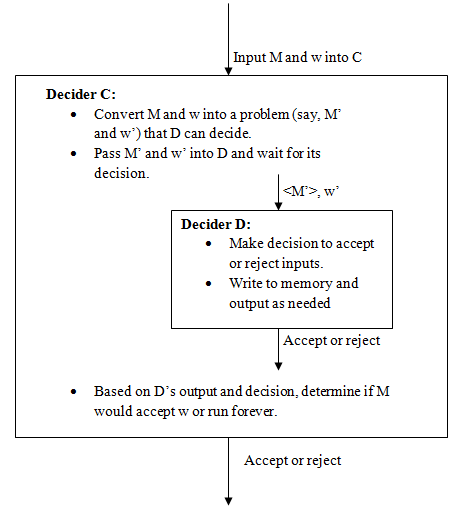

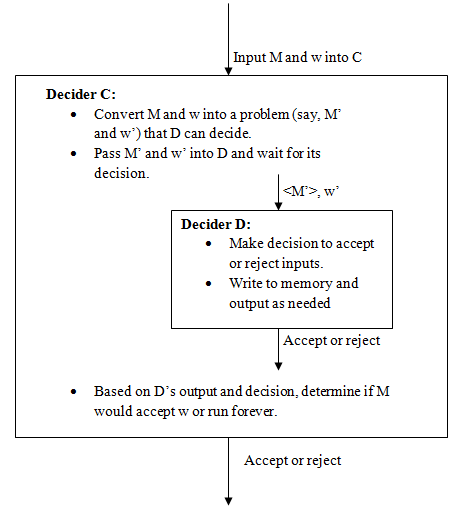

The next step is to construct another machine, say C, that takes advantage of D to somehow decide the halting problem. This relationship is shown in Figure 1 below.

|

C's job is to decide the halting problem for when a Turing Machine M is run on w. C will make some modifications to M and w and pass them along to D. When D makes its decision, C can read D's output and final state of "accept" or "reject". C will now be able to say that the result of D operating on M' and w' will let it decide if M halts on w. Now we're done: If C can use D's computation results to decide if M halts on w, then C has solved the halting problem. But we know that the halting problem cannot be decided, so this result is impossible. So then such a decider D cannot exist, and the language L cannot be decided.

What happens when we run C on Turing Machine M and input w? If M accepts w, then M' will print "GT". If M rejects w, then M' will never print "GT" - we substituted all of the possible "G"s and "T"s with lowercase "g" and "t". If M loops forever, M' will still not print out "GT". So we've solved the halting problem for M and w! But solving the halting problem is impossible, so D could not have decided L (i.e., D could not have decided if any Turing Machine X ever printed out "GT" when given any input y). So L is undecidable.